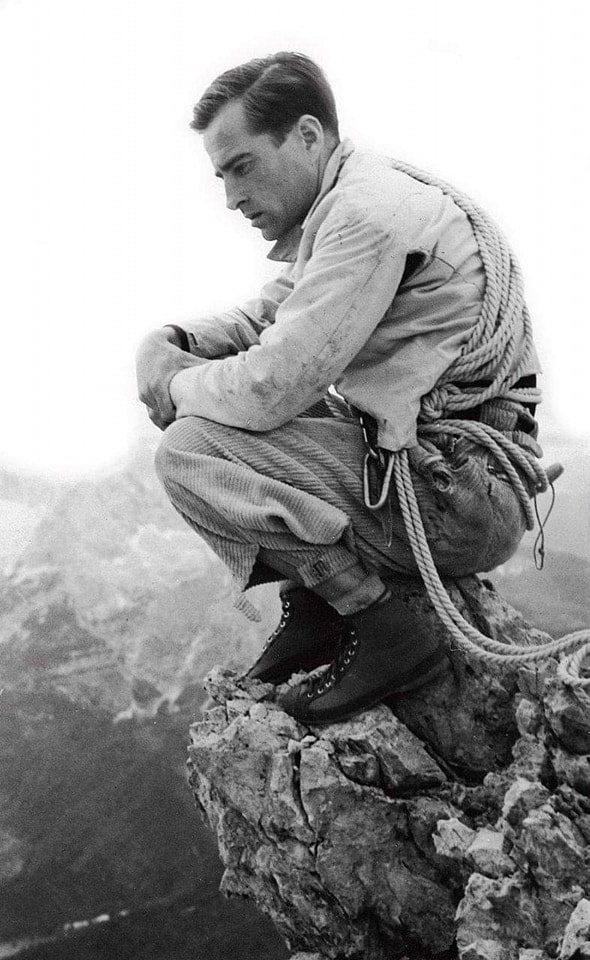

The Angel of the Dolomites

The Dolomites are one of Europe’s most majestic mountains. With their sharp ridges, towering peaks, and sheer walls, the “pale mountains” have attracted climbers worldwide for more than a century. However, Italian climber Emilio Comici defined today's modern climbing in the Dolomites, pioneering some of the most challenging routes in the region.

by Mavi

·

Fri 14 Apr 2023

by Mavi

·

Fri 14 Apr 2023

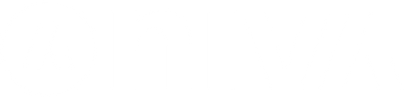

Emilio Comici was not a mountaineer who grew up among the peaks. Born in Trieste on February 21, 1901, to a Veronese mother and a Triestine father, he attended compulsory schools without excelling in his studies and was hired at the age of 15 by the Magazzini Generali of Trieste for a clerical position. Since childhood, he frequented the Pitteri Recreational Center of the National League, and when he turned eighteen and could no longer attend due to age limits, he joined the "XXX Ottobre," a new sports association that practiced gymnastics, athletics, cycling, football, and rowing. A speleological group was added to these sections, and Comici, although excelling in other sports activities, joined promptly.

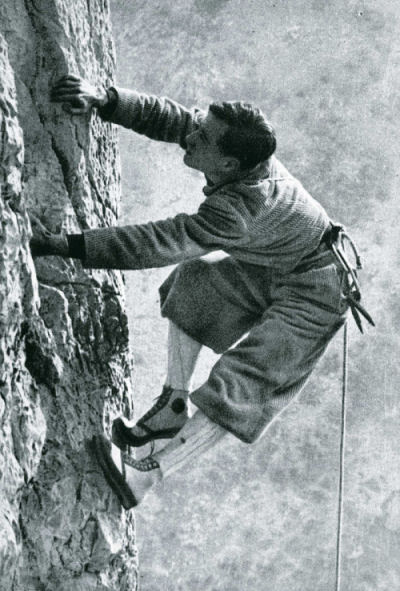

His first contacts with the Alps, therefore, took place in the depths of the karst caves, but when the young Comici accidentally discovered the practice of mountaineering in the mid-1920s, his life changed radically. He began to frequent the walls of Val Rosandra with his friends and progressed so quickly that he founded the first mountaineering school in 1929. He decided that this would be his life and, after much insistence, managed to move to Misurina and become an alpine guide in 1932. In the world of climbers, he immediately became a legend: "Comici suffered and enjoyed the mountain" writes Mario Cecere, "exalted and blasphemed it, dominated it and was afraid of it; he himself was a refined pianist, an eclectic person who drew for himself and for the Alp lovers an ascending and joyful line."

In 1921, Emilio Comici joined the irredentist circles of Trieste and enrolled in the National Fascist Party and from 1938 until his death, Comici held the position of fascist mayor of Selva di Gardena. Indeed, Emilio Comici was a fascist. But his greatness lay elsewhere. Not in politics, not in public life, which he avoided like the plague.

In 1929, together with other climbers from the GARS (Gruppo Arrampicatori, Sciatori) of the Mountain Guides' society of the Julian Alps. He founded the first climbing school in Italy, known as the "Scuola di arrampicamento," under the CAI (Club Alpino Italiano) section in Trieste. After his death, the school was renamed in his honor by the instructors of the time, becoming known as the "Scuola di alpinismo Emilio Comici."

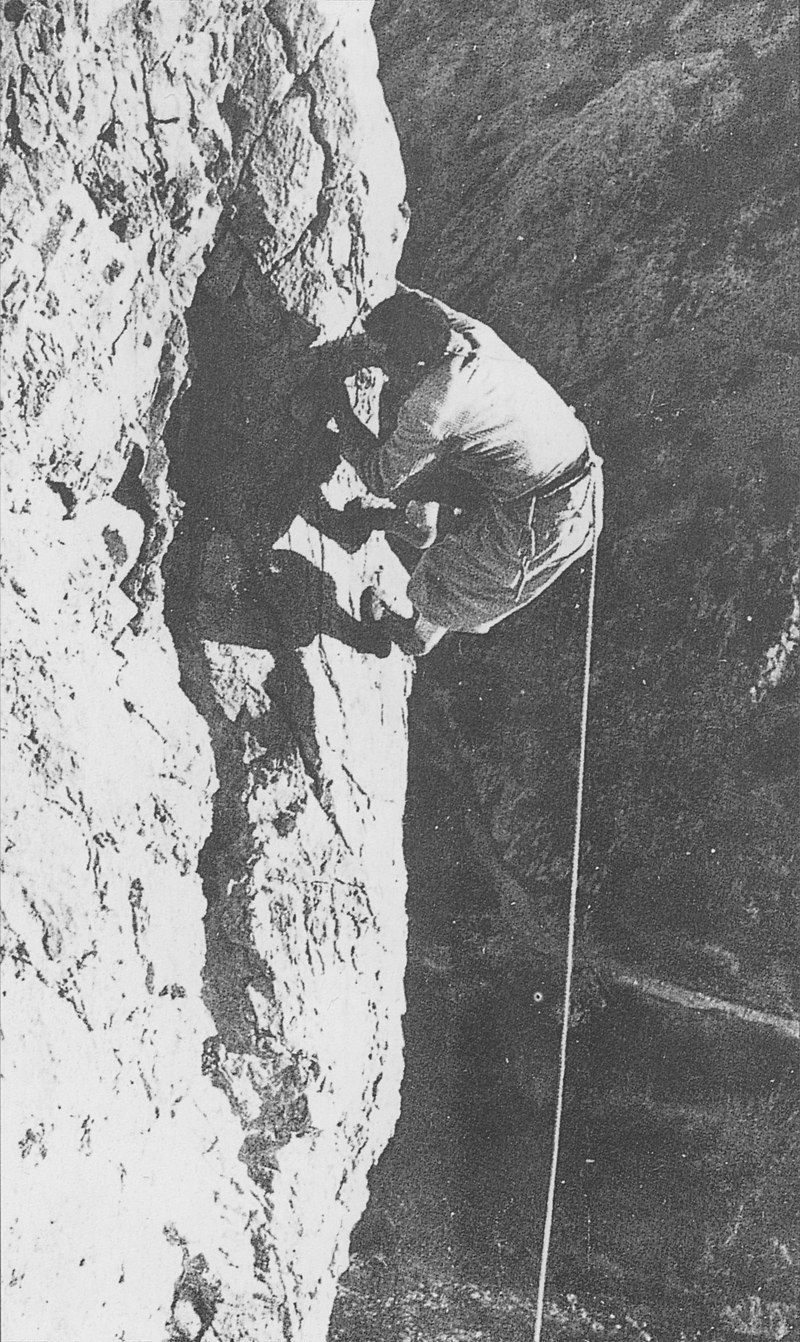

Emilio Comici was one of the greatest climbers not only in Italy, but in the entire international alpine panorama. However, according to some experts, what made him unique and perhaps the best climber ever was his solitary, aesthetic, and mystical interpretation of ascents to the peaks. Recalling the conquest of Cima Grande di Lavaredo in 1937, alone and without ropes, he wondered what he was pervaded by:

"Was it a form of madness or alpinistic sadism, perhaps? I don't know, I was intoxicated, yes, but conscious because I felt the physical strength to overcome the overhang and the moral certainty to dominate the void. I recognize a priori that solo climbing on difficult walls is the most dangerous thing one can do, but what one feels at that moment is so sublime that it is worth the risk."

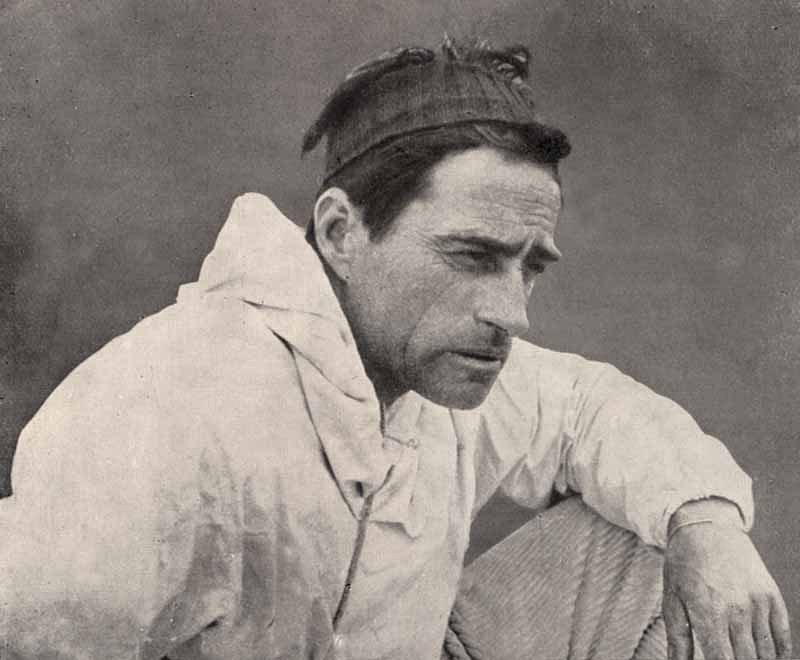

Emilio Comici was a virtuoso of mountaineering, an artist of climbing, a tightrope walker of the rock. But his extraordinary art was not aimed at impressing or eliciting applause, like the trapeze artist in the equestrian circus. And there was no safety net underneath him in case he missed his grip. The heroic and crazy gesture of climbing a wall with the "water drop" technique, choosing the straightest path regardless of the technical difficulties, was an end in itself. It did not involve rewards or lucrative contracts with sponsors, as is the case today in dangerous sports. "We live on sensations, understood in the noblest sense of the word" said the athlete from Trieste. "Everyone has their own, otherwise life would be useless and empty. But to live fully, you must also risk something. That's what Il Duce taught."

As already mentioned, Emilio Comici is a convinced fascist. In theory, he has all the credentials to become a symbol of the Mussolini regime, which celebrates mountaineering as the ideal discipline for the "new man". However, the Trieste climber is also a loner, perhaps even shy, and does not take advantage of his position. It should also be added that he himself appears as a somewhat eccentric character, compared to the rhetoric of the Ventennio. "During bivouacs, he talked to the stars" Cecere writes, "and when he walked on earth and taught skiing, he always appeared different from other men: despite the erotic impulse he felt for the mountains". Comici was not the typical "vitalist" of the time, and it would be pitifully wrong to draw, from the title "Heroic Mountaineering" given to the chronicles of his intrepid climbs, only a conformist toll, with a romantic aftertaste, to a Faustian impulse or a supposed demagogy of the regime".

Those who knew him up close say that there was something religious in Emilio Comici's approach to the peaks. As he himself seems to confirm in this statement: "On the mountains, we feel the joy of living, the emotion of feeling good and the relief of forgetting earthly things; all this because we are closer to heaven".

But fate often plays tricks even on the bravest men. Thus the life of the climber who had risked his life every day on the steepest peaks of the Dolomites ends with an almost banal accident, right in Selva di Val Gardena. It is October 19, 1941, and Comici is climbing a wall for beginners with friends who are not very experienced in mountaineering. Trying to give advice to a friend, Emilio leans out, relying only on a cord, which is not even his. But the rope is rotten, it suddenly breaks under his weight, and he falls for 40 meters. He falls onto a meadow, but to make matters worse, he hits his head on a rock hidden in the grass and dies on the spot.

The Zsigmondy-Comici refuge, located at an altitude of 2,224 meters, is named after Emilio Comici. In addition to his climbing skills, Comici is also remembered for his aesthetic conception of climbing, which he viewed as an opportunity to express oneself through harmonious movement. He wrote the book "Alpinismo Eroico" which reflects the rhetoric of the historical period.

Emilio Comici is also commemorated with the Comici refuge in the Piz Sella-Plan del Gralba area at the foot of the Sassolungo, the Zsigmondy-Comici refuge at Piani di Rio di Sopra under the Croda dei Toni in the municipality of Sesto, the Comici bivouac in the Busa del Banco in the Auronzo di Cadore area, a commemorative stone, and the Emilio Comici National School of Mountaineering of the Alpina delle Giulie section of the CAI in Trieste.