Walter Bonatti on the Dru

Dru, guttural and syncopated sound. A synthesis, at times dramatic, of the aesthetics and mountaineering aspirations of several generations and schools of extreme climbers: 'One of the purest wonders of the Mont Blanc chain', is how the Vallot Guide, bible of Europe's highest mountain, describes it.

by Mavi

·

Fri 11 Aug 2023

by Mavi

·

Fri 11 Aug 2023

The Dru was the place of perfect mountaineering and psychological redemption to the frustration suffered the year before by Walter Bonatti on the other extreme symbol of alpinism: K2.

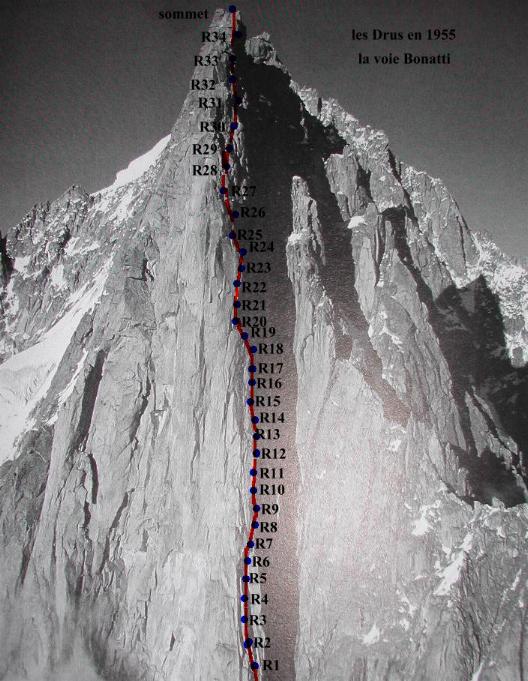

It is 1955, and on 17 August Bonatti begins his solo adventure on the 'Dru Pillar', which from then on will become the 'Bonatti Pillar'.

The solitude

He masterfully climbs the initial and middle part of the wall for four days, always with extreme difficulties, adopting a safety technique that forces him first to climb self-belayed, then to descend by retrieving the pitons and then to climb back up on the ropes. The rucksack is very heavy, the weather at one point breaks down then improves, in the struggle with the granite he gets more than one injury to his hands and arms. It is, however, the psychological burden that is the hardest to carry: "The solitude that accompanies me is so absolute, so hallucinating, that several times I find myself talking unconsciously, making considerations aloud, in short, translating into words all the thoughts that go through my mind. I even find myself talking to the sack, as if it had a soul, as if it were a real climbing partner."

On the fifth day, Bonatti is at the 'red plates', above the grey overhangs that precede the last quarter of the climb. He is at the bottom of an enormous shell with the upper edges protruding over 800 metres of void. His analytical and meticulous brain considers the few possibilities of ascending, decides on a crack to the left, but after 20 metres it becomes impassable.

He hears an 'aerino' buzzing nearby, he sees it, leans out with an arm and a leg, but a white cloud engulfs and hides him; the buzzing goes away and the loneliness becomes even more oppressive.

By midday he is still standing on the ledge where he had bivouacked.

The Petit Dru after the collapse of the Bonatti pillar (signs of the collapse can be seen on the wall with the lighter-coloured rock). Photo @ Francesca Cortinovis

Genius and folly

The idea is brilliant and crazy at the same time. On the right Bonatti glimpses a crack, which he guesses to be of a suitable size to receive the pitons he has with him and which would take him out of the overhangs. But it is little more than an intuition. He could rely on pendulums in the void to reach it. The manoeuvre is daring and unusual, of course, alone then, on that wall - madness! But it is also as rational as Bonatti, who knows that that is the only way out.

There are three 'pendulas' that he makes, for about 40 metres. The last one takes him to an 'aerial step' beyond which the Dru has unexpectedly sucked in a portion of the rocks, grips included. Nothingness, smooth and overhanging, divides him from the saving crack. A return is precluded: the pendulums were descending to the right and ascending them is out of the question. The crack is at 15 metres and total despair, for a whole hour, minute after minute.

Then the flash. The idea is once again brilliant, perverse, daring: it is the only one.

Above him at 12 metres there is an outgrowth of granite blades, they seem unbalanced, precarious, but perhaps not. He thinks and acts: he ties knots in the rope and, like a 'bolas', throws it over the blades in the hope that it will click and hook, but above all that it will support him. 10, 30, 50 attempts. Then finally the rope snaps. It is a an extreme gamble. He secures himself with the other rope, but if something didn't work, it would still be a disaster. He throws himself with his eyes closed, with all his breath in. He holds on, climbs up the rope and finally pours exhausted and congested onto the granite blades that were clearly not so precarious.

Bonatti route depicted in 1955

The crack he had intuited is not there and the wall overhangs, forming a hollow where Bonatti finds the strength to hoist himself up, palm by palm; effectively free climbing. The rope runs out and he has to release the self-belay, holding only the end of the rope. The situation becomes even more difficult when the rope gets stuck and he ends up in an area of 'soft, almost chalk-like' rocks. He plants a series of pitons and entrusts this improbable anchorage with his life as he slips out to retrieve his sack and rope. He is out of the 'big apse', now the mountain will be more benign to him.

Two more pendulums to return just above the starting zone of the whole long manoeuvre and the wall finally 'settles'. It is now dark and he is on a good little terrace. "I now feel that I have the Dru Pillar in my grasp. But above all I feel that I have crossed far more distant and invisible borders. I know that I have overcome the barrier that separated me from my soul, and I still feel, at last, that I have untied my inner knot, a trauma from K2. In the emotion of this moment I realise that my eyes are wet with tears."

It is the sixth day, a few more attempts by the mountain to resist: a boulder comes loose and hits him in the leg, but at 16.37 he is on the summit. Just a glance, no "beatitudes of circumstance". He is the Dru and he knows it, nothing else matters.

This blogpost is a translation of an article appeared on Montagna.tv. We link here the original: https://www.montagna.tv/166979/il-riscatto-di-walter-bonatti-sul-dru/